Breaking Icons – Artwork Jewellery Discussion board

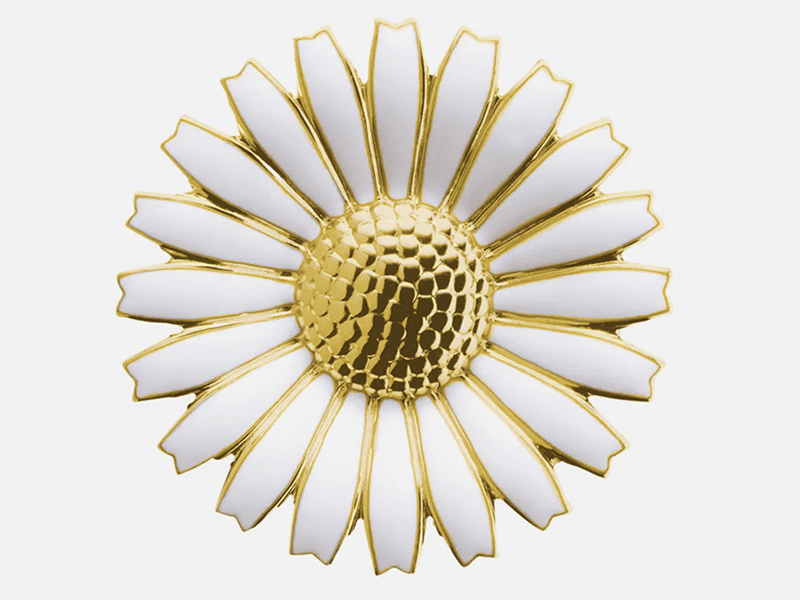

The Georg Jensen Daisy brooch is one among Denmark’s most recognizable items of jewellery. It was designed by Anton Michelsen in 1940 to commemorate the delivery of Princess Margrethe, now Queen Margrethe II. It has since then turn into an emblem of Danish satisfaction and unity. Excess of an ornamental accent, the brooch capabilities as a marker for custom and collective id in a rustic typically cited for instance of societal progressiveness. But Denmark stays one of the vital inaccessible international locations for outsiders akin to refugees and migrants. This placing contradiction reveals dissonance between the nation’s progressive picture and its exclusionary practices.

Artwork and politics typically play hand in hand, and jewellery can act as a robust car for political commentary. As soon as worn, jewellery permits ideas to interrupt exterior the partitions of the standard white dice and enter public life. Danish jewellery artist Kim Buck creates politically engaged items by subverting iconic nationwide symbols. Utilizing objects such because the Daisy brooch, he critiques cultural uniformity and the selective reminiscence that form Danish id.

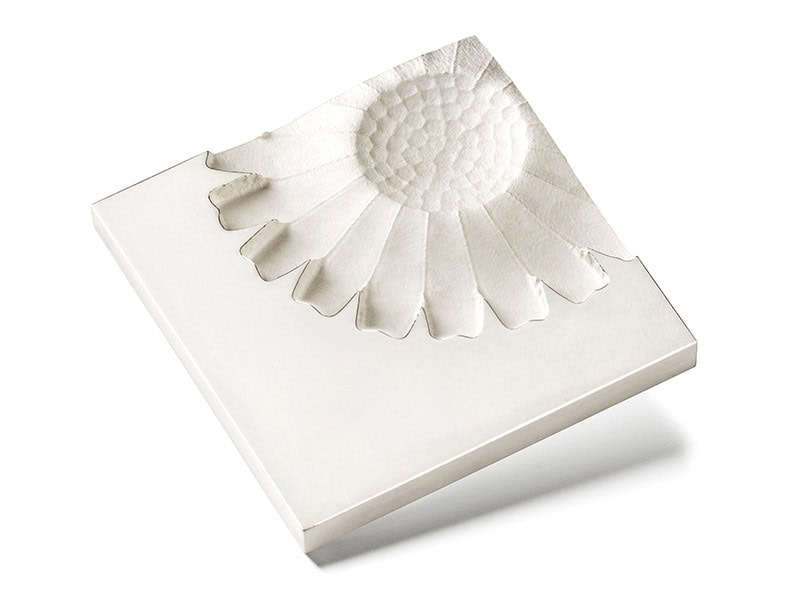

The Daisy brooch, extensively owned and mass-produced, reinforces Denmark’s nationwide cohesion. However such symbols may also obscure underlying complexities and contradictions inside the nationwide narrative. Notably, this is applicable to Denmark’s colonial historical past and the exclusionary elements of its nationwide id. Over the previous 20 years, Buck has appropriated the daisy motif for a number of works. His earliest exploration of the daisy motif goes again to 2003. He created a sequence of three brooches faithfully replicating the Georg Jensen daisy define and imprint. By doing this, Buck was negotiating notions of possession relating to nationwide emblems and id building. Does this particular daisy belong to Georg Jensen, or does it belong to Denmark as a rustic? As a Danish citizen and topic of the Queen, is Buck allowed to duplicate it? Does his nationality and id bestow him particular entry to this floral design?

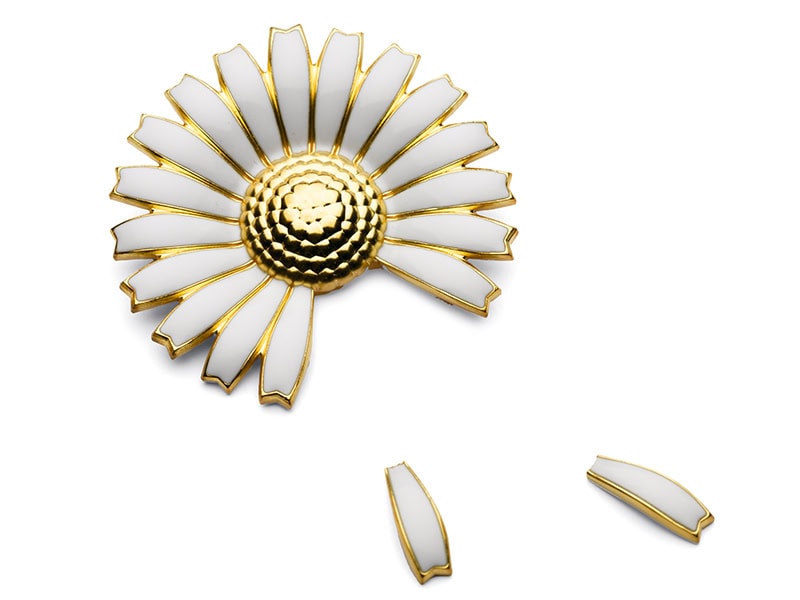

Later, in 2007, Buck escalated this critique. He began utilizing precise Georg Jensen brooches as readymades. One intervention concerned stamping his maker’s mark alongside the unique model’s. Through the stamping course of, some petals fell off. This resulted within the sequence Loves Me, Loves Me Not. The title, as artwork historian Jorunn Veiteberg argues, factors to “each doubt and ambivalence.”[1] This ambiguity might apply to the brooch as a Georg Jensen product. But it surely additionally extends to its symbolic weight as a nationwide emblem and a permanent image of the love Danes really feel for his or her queen. Buck’s intervention thus invitations a broader reflection on the ideological underpinnings of Danish id and loyalty to royal establishments.

To at the present time, Denmark stays one of the vital ethnically homogenous societies on this planet. This issue is usually credited with fostering the event and perpetuation of a robust, politically secure, and unified nation.[2] However as anthropologist Kusum Gopal argues, this notion of unity interprets right into a conception of equality that veers towards a desire for “sameness in each respect.”[3] Distinction is usually met with mistrust, whether or not it pertains to cultural background, ambition, or success.[4] It’s subsequently pertinent to query the Danes’ affection for his or her queen and their approval of monarchy altogether, which epitomizes elite privilege and unquantifiable wealth.

The Georg Jensen Daisy brooch embodies notions of Danish nationwide id, in addition to the conflation between equality and sameness. The queen wears it. Additionally it is present in most Danish households’ jewellery bins. In a rustic that has no official floral emblem, the daisy was even voted Denmark’s unofficial nationwide flower attributable to its widespread possession. This contributes to cementing the brooch’s function as an object of nationwide consensus. As an object commemorating Princess Margrethe’s delivery, it additionally capabilities as a fabric expression of monarchical reverence. Buck’s appropriation strips the thing of its cultural sanctity and reframes it as a commodity. The ensuing sequence, Loves Me, Loves Me Not, provokingly questions the overarching consensus that runs by modern Danish society. It challenges not solely the monarchy but in addition the erasure of Denmark’s colonial legacy. By defacing what’s arguably essentially the most recognizable image of Danish royalty, Buck symbolically confronts the imperial establishment that drove a now-dissolved however traditionally vital colonial empire that has brutally impacted the Caribbean, West Africa, India, and Greenland. These colonial entanglements, typically overshadowed by later British Imperialism, stay absent from Danish public discourse and collective reminiscence.[5] Loves Me, Loves Me Not thus embodies Buck’s ambivalence towards Denmark as a nation and the broader tradition of denial it sustains.

In Daisy, Freely After Niels Heidenreich (2007), Buck furthers his critique. The sequence consists of 4 pendants made by reducing a Georg Jensen Daisy brooch into 4 elements. The title and the thing each level to the notorious theft of the Golden Horns from the Danish royal treasury in 1802 by goldsmith Niels Heidenreich. These Iron Age artefacts have been Denmark’s best gold treasure. Heidenreich unapologetically melted them into miscellaneous jewellery items and poor copies of Indian colonial cash.[6] Buck’s reference to Heidenreich attracts a parallel between historic sacrilege and his personal transgressive gesture. It questions the legitimacy of altering one other designer’s work, however extra importantly, an icon of Danish id. The allusion to the Golden Horns, steeped in romanticized nationalism and imperial nostalgia, underscores how objects can embody symbolic energy past their materials kind. Buck’s fragmentation of the Daisy brooch echoes Niels Heidenreich’s vicious act, sacralising the thing by violation and solidifying his affront to Danish nationwide id and patriotism.

Finally, Buck challenges the idea that jewellery should be static, decorative, and apolitical. As a substitute, he reimagines it as a dynamic kind, able to being reshaped, reinterpreted, and deployed as a car for political critique. By means of humor, he renders his provocations accessible. His use of irony fosters engagement somewhat than alienation. By appropriating and subverting acquainted symbols just like the Daisy brooch, Buck invitations the general public to reassess the values embedded inside them. In his palms, a cherished emblem of Danish custom turns into a software of resistance and reflection.

Bibliography

Sales space, Michael. The Virtually Almost Good Folks: Behind the Fantasy of the Scandinavian Utopia. New York: Picador, 2016.

Brimnes, Niels. Aarhus College. “The Colonialism of Denmark-Norway and Its Legacies.” nordics.data. Final modified January 7, 2021. https://nordics.data/present/artikel/the-colonialism-of-denmark-norway-and-its-legacies.

Gopal, Kusum. “Janteloven, the Antipathy to Distinction: Danish Concepts of Equality as Sameness.” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 24, no. 3 (2004): 64–82.

Veiteberg, Jorunn. The Actual Factor: Jewelry and Objects by Kim Buck. Translated by Arlyne Moi. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Artwork Publishers, 2021.

We welcome your feedback on our publishing, and can publish letters that interact with our articles in a considerate and well mannered method. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; accomplish that right here. The web page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is right here.

© 2025 Artwork Jewellery Discussion board. All rights reserved. Content material might not be reproduced in entire or partially with out permission. For reprint permission, contact data (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] Jorunn Veiteberg, The Actual Factor: Jewelry and Objects by Kim Buck (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2021), 78.

[2] Marilena Geugjes, Collective Identification and Integration Coverage in Denmark and Sweden (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2021), 13.

[3] Kusum Gopal, “Janteloven, the Antipathy to Distinction: Danish Concepts of Equality as Sameness,” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 24, no. 3 (2004): 70.

[4] Michael Sales space, The Virtually Almost Good Folks: Behind the Fantasy of the Scandinavian Utopia (New York: Picador, 2016), 3.

[5] Niels Brimnes, “The Colonialism of Denmark-Norway and Its Legacies,” nordics.data, Aarhus College, final modified January 7, 2021, https://nordics.data/present/artikel/the-colonialism-of-denmark-norway-and-its-legacies.

[6] Veiteberg, The Actual Factor, 78.